Italian Regional Map

Many non-Italians identify Italian cooking with a few of its most popular dishes, like pizza and spaghetti. People often express the opinion that Italian cooking is all pretty much alike. However, those who travel through Italy

Italy

A Roman Banquet in a Triclinium. During much of the dinner, each guest leaned on his left elbow, leaving the right arm free. As three men lay on the same couch, the head of one man was near the bosom of the man lying behind him. The rule was that the number of guests should be no less than that of the Graces (3), nor exceed that of the Muses (9).

During medieval times, the absence of a powerful central authority allowed the creation of many fiercely independent cities. These Comuni, from the Alps to the border of the Kingdom of Naples Italy developed mostly through trade in valuable merchandise, such as spices and fabric, with northern Europe and the East. A rich cuisine developed, offering great diversity from one town to another.

Tuscany Florence Europe , which was on the verge of great transformation due to the discoveries of the age of exploration. The Renaissance initiated a great revolution in the arts, also reflected in spectacular and extravagant new ways of cooking.

for further readings:-http://www.annamariavolpi.com/what_is_italian_cooking.html

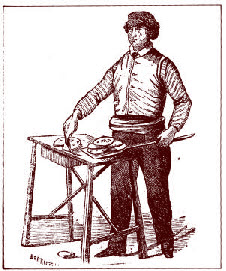

Interior of a Roman Kitchen. Engraving by B. Pinelli, circa 1830.

Not only does each region have its own style, but each community and each valley has a different way of cooking as well.

Every town has a distinctive way of making sausage, special kinds of cheese and wine, and a local type of bread. If you ask people, even in the same area, how to make pasta sauce, they will all have different answers. Variations in the omnipresent pasta are another example of the multiplicity of Italian recipes: soft egg noodles in the north, hard-boiled spaghetti in the south, with every conceivable variation in size and shape.

Perhaps no other country in the world has a cooking style so finely fragmented into different divisions. So why is Risotto typical of Milan , why did Tortellini originate in Bologna , and why is Pizza so popular in Naples

This is so for the same reason that Italy

This diversity stems largely from peasant heritage and geographical differences. Italy is a peninsula separated from the rest of the continent by the highest chain of mountains in Europe . In addition, a long spine of mountains runs north to south down through this narrow country. These geographic features create a myriad of environments with noticeable variations: fertile valleys, mountains covered with forests, cool foothills, naked rocks, Mediterranean coastlines, and arid plains. A great variety of different climates have also created innumerable unique geographical and historical areas.

But geographical fragmentation alone will not explain how the same country produced all of these: the rich, fat, baroque food of Bologna, based on butter, parmigiano, and meat; the light, tasty, spicy cooking of Naples, mainly based on olive oil, mozzarella, and seafood; the cuisine of Rome, rich in produce from the surrounding countryside; and the food of Sicily, full of North African influences.

The explanation is hidden in the past; the multitudes of food styles of Italy Italy

Local traditions result from long complex historical developments and strongly influence local habits. Distinctive cultural and social differences remain present throughout Italy

The Romans politically controlled the territory about two thousand years ago, integrated Greek civilization, and created an empire that laid the foundations of Western civilization. They imported all kinds of foods from all over the known world. Roman ships carried essential foods, such as wheat and wine, as well as a variety of spices from as far away as China Tibet

After the decline of the city states, the territory of northern Italy was partially occupied from time to time by France or Austria Italy Italy , it is in northern Italy Bologna the gastronomic capital of Italy

While the north would see the creation of many small independent political entities, the south of Italy Europe , the south suffered greater poverty and isolation. The people of southern Italy Italy Italy

Dry macaroni is suitable for storing, trading, and transporting. The invention of the bronze press industrialized the manufacturing of pasta, making macaroni affordable. Present in Sicily since Arab occupation, macaroni became extremely popular in Naples Sicily

Local traditions result from long complex historical developments and strongly influence local habits. Distinctive cultural and social differences remain present throughout Italy

Italian Menu Sequence

Meal stage Composition

Aperitivo Apéritif usually enjoyed as an appetizer before a large meal, may be

1. Campari

2. Cinzano

3. Prosecco

4. Aperol

5. Spritz

6. Vermouth

Antipasto literally "before (the) meal", hot or cold appetizers

Primo "first course", usually consists of a hot dish like pasta, risotto, gnocchi, polenta or soup.

Secondo "second course", the main dish, usually fish or meat. Traditionally veal, pork and chicken are most commonly used, at least in the North, though beef has become more popular since World War II and wild game is found, particularly in Tuscany

Contorno "side dish", may be a salad or cooked vegetables. A traditional menu features salad along with the main course.

Formaggio e frutta "cheese and fruits", the first dessert. Local cheeses may be part of the Antipasto or Contorno as well.

Dolce "sweet", such as cakes and cookies

Caffè coffee

Digestivo "digestives", liquors/liqueurs (grappa, amaro, limoncello, sambuca, nocino, sometimes referred to as ammazzacaffè ("coffee killer")

Aperitivi

A meal should start with an aperitif: a small drink to “get the juices flowing”. This need not be alcoholic, but generally speaking the drink should have a “bite” and be more bitter than sweet. Examples include Campari and Soda, Dry Martini, Pastis and Gin and Tonic.

Pane

It is usual to have bread and Grisini (breadsticks). Italian bread is more elastic, and has a thicker, harder crust than English or French. It is perfect for dipping into a little dish of olive oil which is sometimes offered (or asked for!). Olives are commonly offered with the bread, and go well with the aperitif.

Garlic Bread

Usually Pizza-base style, sometimes offered with a topping of tomato puree, or cheese.

Vini

I’m a bit of a neophyte when it comes to wine, though I admit to favouring Italian style wines over most others. I personally like a really full bodied, powerful red wine, probably because I like full-flavoured meals in general. Italy provide so many excellent wines, with the D.O.C.G. classification being granted to: Albana di Romagna, Asti, Barbaresco, Barolo, Brachetto d'Acqui, Brunello di Montalcino, Carmignano, Chianti, Chianti Classico, Franciacorta, Gattinara, Ghemme, Montefalco Sagrantino, Moscato d'Asti, Taurasi, Torgiano Rosso Riserva, Vermentino di Gallura, Vernaccia di San Gimignano, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano.

Primi (piatti)

Antipasto – literally “before a meal”, and not, as I used to think, before the pasta course (Latin: Ante, before, Italian: Pasto

Typically Italian starters:

Bruschetta

Toasted bread, drizzled with hot olive oil, covered with pieces of fresh tomato. I recently had “Bruschetta Fegatini” which consisted of toast – made with Italian style bread – covered with chicken liver pieces sautéed with a hint of chilli (pepperoncino). Absolutely excellent for “starting your motor”!

Carpaccio

Wafer thin slices of prime beef, served raw with a dressing of vinaigrette, or simply good olive oil and shavings of fresh Parmesan.

Prosciutto

This uncooked, dry-cured ham is exquisite. Parma and San Danielle are the famous producing towns, though I have heard of “Culatello”, from Zibello, and a few other communities within Parma

Salumi (salami)

Salame, Bresaola, Pancetta, Mortadella. There are more types than you can shake a stick at. A selection is often on the menu as an antipasto.

Fagioli e Tonno

Cannelini beans and Tuna, olive oil, lemon juice, a little sliced onion, a touch of garlic, salt and pepper. Served cold. The use of tinned, pre-cooked beans and tuna should not deter you – there is not much a canner can do wrong with beans or tuna! The dish does rely, however, on really good olive oil, and fresh garlic and lemon.

Tomato and Mozzarella Salad

Slices of large, ripe, tasty tomato, interspersed with similarly sized slices of Mozzarella, drizzled with olive oil and garnished with fresh basil leaves. Make sure you get Buffalo

Soup, Pasta or Rice Dishes

These are considered starters, but lately, the despicable trend to rushing meals has relegated them to main courses!

- Minestre, Minestrone, the “big soup”. Soup was originally only for the poor, and the clergy would “minister” to them by ladling it out of large cauldrons.

- Spaghetti, Macaroni, Linguine, Gnocchi, Lasagne, Penne, Farfalle, Canneloni, all can be served with various sauces, often based on tomato, but could instead be based on basil and pine-nut kernels, cream and pancetta or even salmon and chillies!

- Risotto, a northern Italian dish, creamy textured short-grain rice (such as Arborio) carefully prepared to absorb the flavours of the liquids used – broth, wine, butter, olive oil.

Secondi

Pesce - Fish

Seasonal, fresh, fish and seafood. Delicacies include Squid in its own ink, Octopus, Astice or Arragosta (Lobster).

Baccala – dried, salted fish, usually cod. Often served battered.

Carne - Meat

Offal - in particular liver, Tripe, Wild Boar, Preserved meats like Cacciatore sausage, Horse, Rabbit, Veal.

Contorni – Vegetables and other side dishes

Besides “ordinary” vegetables: Potatoes, Cauliflower, Broccoli, and so on, the Italian menu features delights such as Artichokes (Carciofi), Aubergines (Melanzane), Zucchini (and their flowers), Peppers (Pepperoni), Fennel (Finnochio). Funghi (mushrooms) – Porcini are renowned, especially fresh. Truffles are just as much – even more – a part of Italian culinary folklore as French.

Insalata

Traditionally served after the main course, perhaps to clear the palate for the rest of the meal.

Frutta - Fruit

Fresh fruit – possibly including dried fruit and nuts – served as a separate course, not as an alternative to the dessert.

Dolci - Sweets

Well-known offerings are “Torta della Nonna”, “Zuppa Inglese” and “Tiramisu”. If you get the chance, ask for a real Zabaglione – made with fresh egg yolks, sugar and Marsala wine at the table in a large copper bowl. Do not be fobbed off with a frozen or pre-prepared zabaglione. (Note. Many establishments will not prepare this dish, citing health concerns about the use of raw eggs. Perhaps a wise precaution, but a real shame – they should get their eggs from a known, good, source.)

“Cantucci” (little crisp almond based biscuits), to dip into your glass of “Vin Santo” (“Holy Wine” - a sweet dessert wine)?

Formaggi

Famous examples are: Dolcelatte, Pecorino, Gorgonzola, Mozzarella, Provolone, Ricotta.

Digestivi

The most typically Italian digestif is probably a Sambuca. Customarily (in England

Grappa, the Italian equivalent of Brandy, is also common. However, my uncle, a Sardinian, reckons that grappa is “sub-standard”, being made from the dregs – skins and stems - remaining after winemaking. He insists that Aqua Vita, distilled from the juice of grapes – without dregs and stems - is far superior. Having samples of home-made grappa (home distillation is legal in Italy

There are numerous other Italian liqueurs – too many to mention, so try a different one each time.

A non-liquid digestif is “Spaghetti, Aglio, Olio e Peperoncino”: spaghetti served simply with a dressing of olive oil in which garlic and chillies have been fried. Perhaps a light topping of freshly grated Parmesan.

Café

Espresso, Cappuccino, Latte, Latte Macchiato (Hot milk with a dash of espresso), Caffe Macchiato (an espresso with a dash of hot milk), Freddo, Americano, Corretto (with a shot of liqueur), Ristretto (to be taken intravenously!) All require the use of really good beans, really well roasted, really well ground. Cappuccino is frowned upon any later than breakfast.